The lunar cycle and the next supermoon: Understanding the many phases of the moon

Few sights are as universally captivating as a full moon rising into the night sky. For many of us, stepping onto a balcony or looking up from a quiet street to admire it feels almost instinctive.

Call it romance or simple curiosity, but that glowing disk overhead has fascinated humanity for as long as we have looked skyward. What we often forget is that the full moon is just one of many appearances the moon takes as it journeys around Earth.

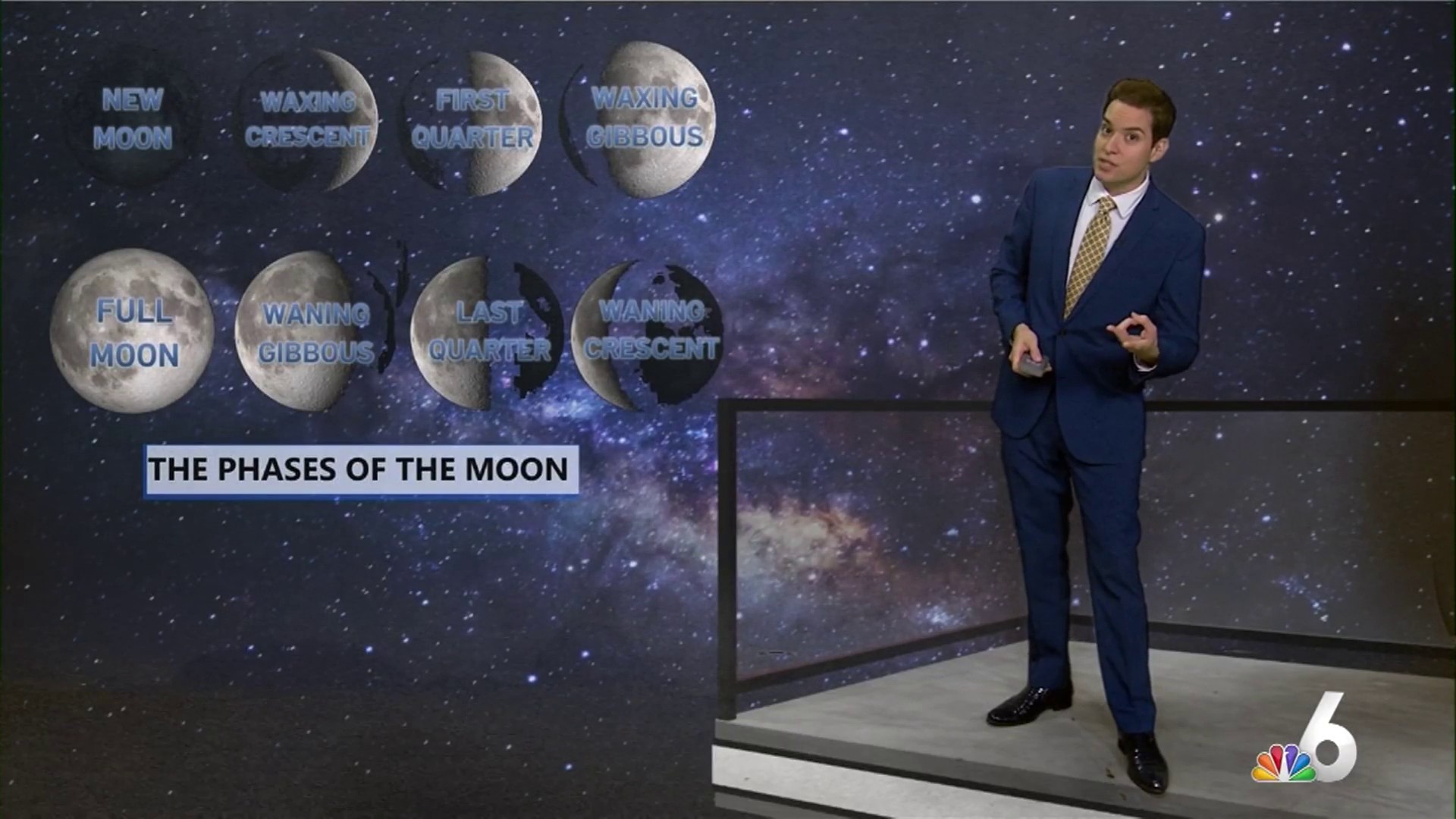

As the moon orbits our planet, we observe eight distinct phases, each revealing a different fraction of its sunlit surface. Together, these phases form what we know as the lunar cycle.

What are the phases of the moon?

The cycle begins with the new moon. At this stage, the moon is positioned between Earth and the sun, meaning the side facing us receives virtually no sunlight. The moon is there, but it is almost invisible in the sky.

Over the following days, a thin sliver of light appears. This phase is known as the waxing crescent, when the illuminated portion of the moon gradually increases. Waxing simply means growing in illumination.

Next comes the first quarter. Despite the name, this phase does not mean the moon is one-quarter full. Instead, half of the moon’s visible face is illuminated. The term quarter refers to the moon having completed about one quarter of its orbit around Earth.

As more sunlight reaches the moon’s Earth-facing side, we enter the waxing gibbous phase. The moon now appears almost full, but not quite. Eventually, the sun fully illuminates the side we see, producing the full moon, when 100% of the visible lunar disk is lit.

After the full moon, the cycle reverses. The illuminated portion begins to shrink during the waning gibbous phase. This leads to the last quarter, when once again half of the moon’s visible face is illuminated, followed by the waning crescent, a thin arc of light that many people liken to a delicate banana shape in the sky. The cycle then returns to the new moon, and the process begins again.

Each of these eight phases lasts roughly three and a half days, completing a full lunar cycle in about 28 days. This timing explains why lunar calendars are based on a 28-day cycle, differing from our standard calendar months, which vary between 30 and 31 days, with February being the notable exception.

One question often arises. Why do we always see the same face of the moon? The answer lies in a phenomenon called tidal locking. While it sounds technical, the concept is straightforward. The moon rotates on its axis at the same rate that it orbits Earth. In other words, it takes the moon about 28 days to spin once and about 28 days to circle our planet. Because these motions are synchronized, the same hemisphere always faces Earth. The moon does rotate, it just does so slowly and in perfect step with its orbit.

What is a supermoon?

From time to time, the moon appears especially large and bright, producing what we call a supermoon. This happens when a full moon coincides with perigee, the point in the Moon’s orbit when it is closest to Earth. The Moon’s orbit is not a perfect circle but an ellipse, meaning its distance from Earth varies.

At perigee, the Moon is typically between 221,000 and 230,000 miles from Earth, compared with apogee, its farthest point, which is close to 252,000 miles away. When a full moon occurs near perigee, it can appear up to 14% larger and about 30% brighter than a typical full moon, although the difference is subtle to the naked eye.

Earlier this January, we experienced the Wolf Moon, named after historical accounts of wolves howling during the cold winter nights. It qualified as a supermoon because it occurred near perigee.

The next supermoon will require some patience. The next one is expected around Nov. 24 and will be known as the Beaver Moon. Why it carries that name is a story rooted in seasonal traditions and history, best saved for another time.

For now, every glance at the moon is a reminder that even familiar sights are part of a precise and predictable cosmic dance. From crescent slivers to glowing supermoons, the moon continues to shape our calendars, our tides and our sense of wonder, well beyond the forecast.