Most San Diego County school districts aren't documenting all student searches

If a school principal in San Diego County demands to look through a student’s backpack and doesn’t find anything against the rules, in most cases, no record will be made about the search.

Civil rights advocates in Southern California say that’s a problem.

If we don’t have the data … let’s say, demographic information … it’s harder down the line to determine: Are these schools and these school districts targeting specific groups of students?Irene Rivera, American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California

Last year, NBC 7 Investigates spoke with Michael Stewart, the parent of a former San Diego Unified student. His son was searched by a Patrick Henry High School administrator when he was a senior.

After that happened, Stewart discovered the district wasn’t following its own policy to document searches. He submitted a public records request for student search data, but the district told him it didn’t exist.

“It was shocking,” Stewart told NBC 7. “If they’re going to, again, take away a child’s liberty — albeit shortly — to search them, that they had no idea how often they were doing it or what they were yielding.”

San Diego Unified’s own policy states they will, “Document or keep records on the basis for the search.” That wasn’t the case when NBC 7 Investigates spoke with Farshad Tabeli, who runs the district’s Office of Investigations, Compliance and Accountability.

Tabeli said the district couldn’t say for sure what kinds of information individual schools were recording.

“I didn’t do an audit of every school and how they’re documenting,” Talebi said. “So that’s where I don’t necessarily feel comfortable saying some sites were doing it right, some sites were not doing it right.”

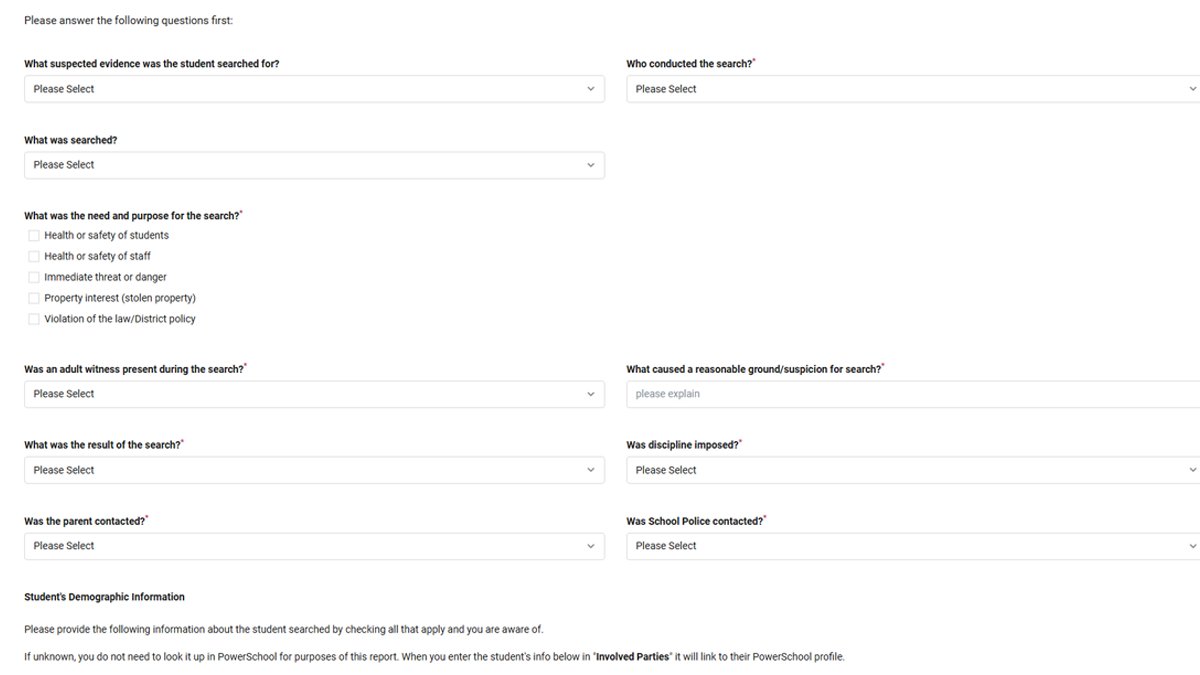

After Stewart reached out, the district made changes mandating that administrators fill out an electronic form for every search. That includes data fields about the reason for the search, who conducted it and what they found, as well as information about the student’s ethnicity and gender.

“I think collecting that data is very important,” Irene Rivera with the American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California told NBC 7.

The senior policy advocate said data collection was instrumental in the ACLU’s effort to end randomized student searches in Los Angeles six years ago. Rivera acknowledged that administrators should have the ability to search kids to keep schools safe.

“We cannot forget that, just because they go into a school, it doesn’t mean they automatically lose all their rights,” Rivera said. “They’re like, ‘OK, they just spent like 10 minutes of my day searching me, going through my items.’ And I have to go back to class and pretend everything is fine and go back to my learning.”

There aren’t any laws on the books in California that require school districts to document searches or how they record information.

“It is for the benefit not only for the schools themselves but, again, for the families who have children who attend these schools,” Rivera said. “Yes, it’d probably be a little bit more tedious work for schools, but I think it’s a necessary step for them to take.”

School districts that require all searches to be documented

There are 42 public school districts in San Diego County. Other than San Diego Unified, only the Chula Vista Elementary School District has a written policy about documenting student searches.

NBC 7 Investigates reached out to all the local districts to find out what each may be doing to document searches, beyond written policies. What we found varied wildly.

Of the districts that returned our requests for information, a total of six said they document every search. Like San Diego Unified, most fill out a form.

Forms for the Chula Vista Elementary School District and the Alpine Unified School District require administrators to detail the reason for the search, who conducted the search, what was or wasn’t found, when parents were notified and what disciplinary action was taken.

The Cajon Valley Union School District also has a form, but it isn’t as detailed and just contains a few blank fields where administrators can write as much, or as little, as they choose.

The Oceanside Unified School District and Escondido Union High School District don’t have a specific form that gets filled out. Instead, administrators must document all searches with a student information portal.

School districts that require some searches to be documented

Twenty-four local school districts said they only make a record of a search if school rules/laws are violated, if the administrator finds drugs/weapons/contraband, or if the student is disciplined.

Those districts don’t have a specific form that’s completed when that happens but told NBC 7 Investigates that some amount of information is entered into the individual student’s file.

That’s also the case for the San Diego County Office of Education. While not a school district, per se, it does operate a few schools and programs.

Rivera said documenting searches that only involve wrongdoing doesn’t show the complete picture.

“If we don’t have the data … let’s say, demographic information … it’s harder down the line to determine: Are these schools and these school districts targeting specific groups of students?” Rivera said.

School districts that don’t document searches or didn’t reply to NBC 7 Investigates

Two local school districts told us they don’t document searches specifically. The Spencer Valley School District cited its small student population as the reason why it’s never needed to develop a documentation system.

The Encinitas Union School District also said it doesn’t document searches. A spokesperson said that information isn’t recorded, even within an individual student’s file.

Eight local school districts never returned our requests for information. That included calls and emails to communication staff, district leadershipand school board members.

Two other districts wouldn’t go into details about documentation. The Sweetwater Union High School District would only share its written search policy, which didn’t contain that information.

The Vista Unified School District wouldn’t answer our questions about documentation, saying it related to school emergency procedures. However, it said all matters of student discipline are documented in accordance with the law.

A lack of analysis of student search data

Documenting searches is one thing. Analysis is another. A few local school districts say they review searches regularly, but no district told NBC 7 Investigates that it was compiling search data to potentially find trends about the kinds of students they’re searching or which administrators are involved.

“I think there’s a lot more positives that would come out from spending a little bit extra time analyzing this data, putting it together, making it readily available for parents, even if not many of them might not be asking for it at the moment,” Rivera said. “Because we want to make sure that our students feel safe, that they feel supported and that families can trust their campuses to treat their students with dignity.”

How districts develop their policies

NBC 7 Investigates reached out to the California Department of Education to see if the state offered districts any guidance on how student searches should be documented. A spokesperson said that’s left up to the districts.

The San Diego County Office of Education echoed that sentiment, saying it’s up to individual school districts to govern themselves, including the development of policies. Neither offers specific guidelines about policies, other than indicating that districts need to follow state laws.

However, NBC 7 found there is one organization leading the way to set school policies statewide: the California School Boards Association. It told us that roughly 95% of California school districts are paid members.

For a fee, the nonprofit group provides a variety of services to districts, including writing policies that districts can choose to adopt. That explains why all the student search-and-seizure policies across San Diego County’s 42 districts are nearly identical in language.

A spokesperson for the association told NBC 7 that it wasn’t working on any new policies about documenting searches and has no plans to, unless lawmakers pass new laws on the subject.

The spokesperson wouldn’t say which local districts were members or how much they paid in dues. However, they say fees were based on the district’s size.

The CSBA provided this written statement:

The California School Boards Association (CSBA) supports local school districts and county offices of education by providing sample board policies and administrative regulations that reflect current law and established legal standards. CSBA does not set nor enforce policy; governing boards decide whether and how to adopt policy language and administrative procedures based on local needs and legal guidance.

Administrative searches of students in California public schools are governed primarily by constitutional law rather than a single, comprehensive statute in the education code. Since there is no single, universal education code provision that requires school administrators to create the same level of documentation for every search, documentation practices vary according to local policy and implementation.

CSBA’s commonly used sample Board Policy 5145.12 (Search and Seizure) language is generally focused on when and how searches may occur, as well as on guidelines for parent/guardian notification. CSBA recognizes that documentation can play an important role in transparency and accountability and informs districts interested in more comprehensive documentation that they may enshrine this practice in locally adopted board policies and administrative regulations developed in consultation with legal counsel.

Because California law provides flexibility in this area, the absence of a statewide mandate does not prohibit districts from adopting stronger documentation requirements. Instead, it reflects local control over how best to balance student rights, staff capacity and administrative consistency.

This story uses functionality that may not work in our app. Click here to open the story in your web browser.